The Startle Reflex in Humans

What Happens When Something Makes us "Jump"?

One of my all time favorite, and much re-visited, scientific articles on understanding stress responses in humans is “Dissociation Following Traumatic Stress: Etiology and Treatment”, which I have mentioned once or twice before:

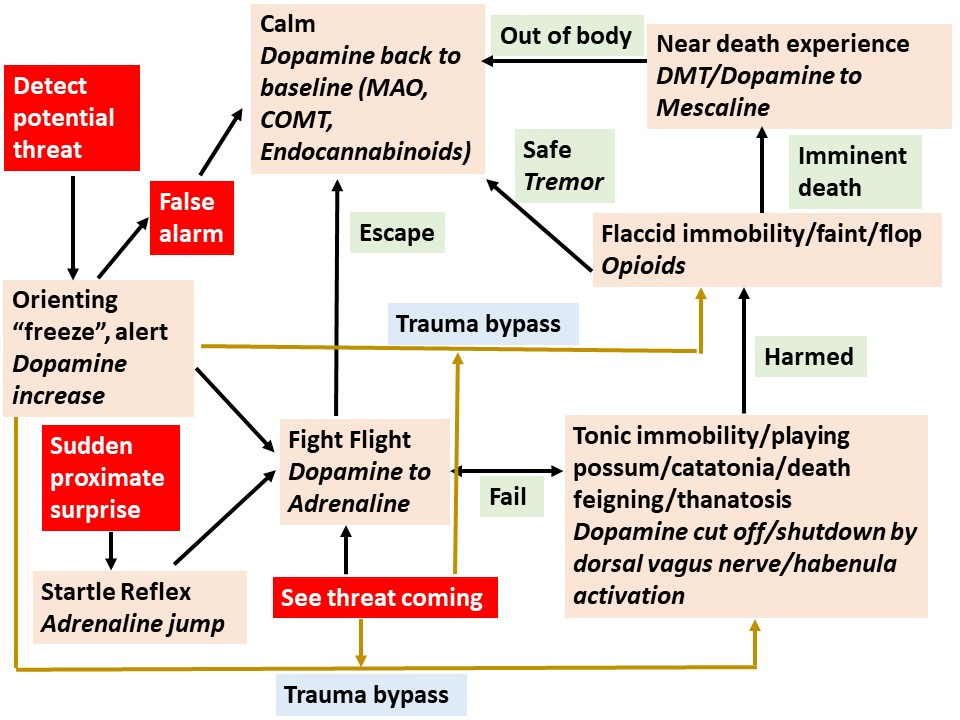

In particular, the escalation of stress reflexes in response to a perceived threat coming closer, which the authors of the article call the “Defence Cascade”, has been instrumental in my own mapping out of our human behaviours and responses to stressors. The current draft of my map is here:

I will cover this map in detail in future articles.

However, there was one aspect of the above mentioned article that I was never clear on. In their Defence Cascade, the process begins with a type of freeze called the “Orienting Response” or “Attentive Immobility”. Think of a deer in the woods, which upon hearing a sound, stops chewing, turns it eyes and ears towards the source of the sound and stands motionless. The authors go to some length to distinguish this Orienting Response from another stress reflex which they call the Startle Response:

“The fight or flight response is preceded by a response with a varying period of time known in ethology as freezing behavior or in psychophysiology as OR. It is characterized by information gathering and the activation of a set of bodily responses that assist in processing the stimulus and may prepare for further stages, sometimes referred to as hypervigilance or hyperarousal: being on guard, watchful, alert, ready to respond.”

“Contrary to the classic stress response model and in line with the defense cascade perspective, studies have consistently found that the initial reaction to aversive stimuli is characterized by a decrease rather than an increase of heart rate and is accompanied by an inhibition of the Startle Response. This ‘‘fear bradycardia’’ (attentional or alerting response) includes motor inhibition, focused attention to the threat, and decelerating heart rate”.

Apart from the differences in heart rate between the two responses, I could not find much information about what the Startle Response actually looks like, or consists of, and hence I did not have clear idea of what is being suppressed by the Orienting Responses.

My main interest in knowing about this, is because, like other stress responses, folks can get stuck, sensitized to, or habituated to, these kinds of reflexive states, and this can manifest as symptoms.

So I began to search for videos of people undergoing the Startle Response, but could not find anything much. I then struck gold when I searched youtube for “making people jump”! Suddenly, I had an enormous amount of data on what the Startle reflex actually looks like. Here is just one video with a plethora of data points.

Taking an amalgam of all the responses, the main features seem to be: a wide open mouth, the arms coming up in front of the face, palms often facing outwards, with jerky motions a bit like a quickly damped tremor [similar to what you see with the Moro reflex in babies:

].

The response also includes literally jumping off the ground, or ducking down, followed immediately by moving away from the source of surprise [flight], or moving towards it [fight]. If the source of surprise remains touching the person, they stay in an extended reflex response, until they have brushed it off or escaped the proximity.

Subsequently, someone recommended I look at photos from Haunted Houses. This was a good call, and I found the article “27 Photos of People Completely Losing Their Minds in a Haunted House” in Cosmopolitan. This captures people right in the midst of their reflex instincts. Again, almost universally is the wide open mouth, but also in these images we see wide open, even bulging eyes. Also universally here, the shoulders are raised, and the arms are in front of them, but they are also all ducking into a crouch, which could be something to do with the positioning of the source of the Startle, that seems to be near the ground.

The wide open mouth intrigued me, not least because the mouth hanging open is often seen in folks with a Parkinson’s diagnosis. I asked a couple of experts about what they thought the reason for this as part of the Startle Reflex was, and got the following feedback:

“like a cat - trying to be as big and scary as possible”;

“open mouth, fear release (release lung, open chest, stability-protect be strong) - the dialectic of attack, fight against - a phylogenetic reaction stereotype in us all”;

I also wonder if it is connected to Stanley Rosenberg’s rapid clamping down of the C1 and C2 vertebrae as the mechanism for very quickly switching between calm/relaxed states and stress responses and reflexes, as covered in his book “Accessing the Healing Power of the Vagus Nerve: Self-Help Exercises for Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, and Autism”.

As for the cats, I looked for, and found, videos of the Startle Response, in felines, and while I did not really see the open mouth response there, I did see that startle really makes cats jump!

As you will see from my draft diagram above, I have now added the Startle Response to my map of stress responses, as an alternative starting point to the Defence Cascade from the Orienting Response. It seems that proximity of the threat when it is first detected is the major deciding factor for which of these Responses is triggered: very nearby it is Startle, and some distance away still, it is Orienting.

There may be a pragmatic application in deliberately causing the Orienting or Startle response. As a person with a Parkinson’s diagnosis, I have noticed that when something make me jump, when I nearly trip or fall, or I stub my toe, say, my symptoms in that instance disappear. I believe this is because folks with Parkinson’s diagnosis are stuck in a later part of the Defence Cascade, in particular, the Tonic Immobility stage. By triggering the Orienting or Startle Reflexes, this results in temporary exit from Tonic Immobility back to the start of the Cascade,

My hypothesis, therefore, is that by repeatedly purposefully resetting the Defence Cascade back to the start by triggering Orienting or Startle, may help to get out of being stuck in a later phase of the Cascade, and result in prolonged symptom relief. Indeed, I recall a study on folks with a Parkinson’s diagnosis, where they modified a treadmill so it was randomly stimulating trips and stumbles. After sessions on this treadmill, the participants got prolonged relief from their symptoms.

For more on the Nervous System in Chronic Conditions, try my online course:

Thanks Gary

In regards to the treadmill with varying speeds, I use a vibration plate at home that oscillates and vibrates and changes speed and intensity throughout the various programs for this benefit (and for other benefits such as bone density, circulation, lymph circulation, muscle confusion).

It seems to me there was a study or article about the benefits of riding on trains for people with Parkinson’s for the same reason. (Can’t find it at the moment.)